I said I would not forget, and I want to write to you, disembodied totem spirit of an ex-thing that I probably don’t believe in, because I want to bear witness, to envision the end of an existence.

It was, of course, absurd. My friend reminded me of this as we waded out to a bench on the edge of a flooded pond carrying a paper replica island towards a herd of confused and curious swans. How could it be otherwise?

Firstly death just is. At an individual level – not in a jolly Halloween cartoon Grim Reaper way, but in a deep epistemological way. We humans can’t comprehend the absence of existence. And we don’t like it. It unsettles us.

It is a further step to imagine the death of something that you didn’t know existed in the first place. That is a loss of opportunity. But also a leap into a gap which the imagination or unconsciousness might fill with projections. My own are of failing to protect something innocent and precious. Was that really you, Bramble Cay Melomys?

I also spend time thinking about rats. Attentive readers will have noticed in the sister post how quickly I conflated the unknown extinct rodent with the common rat. The analogy becomes more problematic when we consider that the survival of the melomys, until climate change finally did for it, occurred mainly because occasional human visitors to Bramble Cay had failed to bring with them the opportunistic and competing rodents which had caused the extinction of other ground-living island dwellers in the area. Real things are always fucking up our best metaphors. But still, as a familiar example of undervalued beings in our midst, rats work pretty well. We are to be observed by several as we launch our craft.

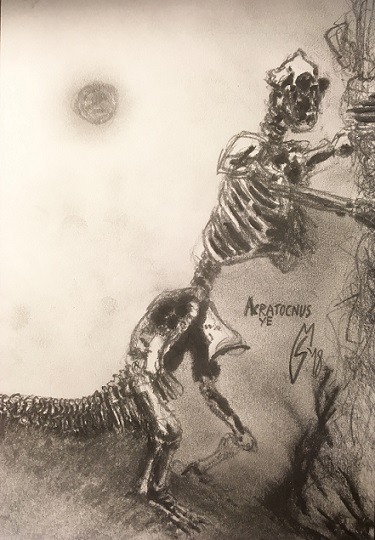

Around the time of the commemoration I saw an artwork by Marcus Coates. Entitled Extinct Animals it is composed of plaster castes of the artist’s arms, hands or even fingers as he makes shadow figures of various extinct animals. Some of these are frankly very schematic, but that doesn’t really affect the impact much. These creatures no longer cast a shadow, so…

I’ve been drawn to Marcus’ work for several years and soon afterwards I was able to see him talk about it. He described his fascination in embodying a message of communication of some kind – and I’ve noticed that this is often across a barrier of some sort, of time, kind, language or even, and often, species. I’ve watched him being interviewed as a Blue Footed Booby on Galapagos TV, attend a community meeting in a condemned council block wearing a deer skull on his head before going into a shamanistic trance, choreograph a number of volunteers sitting in their cars, living rooms and waiting rooms into a replica of the dawn chorus, and take a question from a man dying in a hospice on a journey to and from an ageing woman in a hut in the Peruvian Amazon. Here he is, encouraging a Canadian island community to apologise to the extinct great auks which used to live there.

None of these admirable projects look anything other than absurd. But they do encourage a way of connecting which is uncanny, disorientating and affecting. I think they tug around our felt senses.

Within the growing field of climate anxiety is a recognition that our response to the evidence of climate change is also necessarily un-canny, and will feel at least some part absurd.

We have the notion that Tim Morton draws from object-orientated ontology of the ‘strange stranger’, the thing that we can only encounter in a phenomenological way without prejudice or preconception, and the hyperobjects he develops from that way of thinking ( I’d suggest that extinction is another hyperobject that is spreading through us at the moment, like a lump of indissoluble plastic). In the more cautious and classical philosophical position laid out by Jonathan Lear in Radical Hope,

We do not have to agree with Plato that there is a transcendent source of goodness – that is a source of goodness that transcends the world – to think that the goodness of the world transcends our finite powers to grasp it. The emphasis here is not on some mysterious source of goodness, but on the limited nature of our finite conceptual resources. This, I think most readers will agree, is an appropriate response for finite creatures like ourselves. Indeed, it seems oddly inappropriate – lacking in understanding of oneself as a finite creature – to think that what is good about the world is exhausted by our current understanding of it. Even the most strenuously secular readers ought to be willing to accept this form of transcendence. (pp.121-2, 2006)

Lear’s ‘hero’ ( I think that is fair), the Crow chief Plenty Coups, uses a dream he has interpreted to suggest that his tribe should give up their traditional virtues, and find an accommodation with the crushing forces of American colonisation, which would (and indeed did) allow them to retain their identity and integrity. His message, however, is that in a situation when our known virtues clearly no longer protect us we must search beyond.

We must find new ways of thinking – whether these come to us from overlooked Indigenous traditions, cyber-identities, art practice, experimental philosophies or paradigm shifts in science. All of these are fruitful responses to the crisis of the Anthropocene.

As, I think, psychogeography might be. Psychogeography is a child of situationism, but has been dallying with shamanism for a while too. Being inhabited, haunted, dealing with the margins, and the supplements are the business of our trade – using the tricksterish slogan of ‘Seeing Things As They Really Are’ (@Tim Smith) which suggests we live in an illusion of some sort, and that our imaginations might find a reality that is somehow missing (although of course what is missing might in fact be our imagination).

So digging into this methodology I decided I wanted to create a funeral representation of the absent and unknown creatures.

I don’t actually have these kinds of craft skills – which is, of course, entirely the point. We end up with a green paper tray covered in straw and leaves I gathered from the edges of a new semi-permanent floodpond near my home, some sugar mice purchased hurriedly in something that felt like a drug deal from an olde sweetie shop, and used to mould others out of moss and used kitchen towels, purslane seeds (which apparently grew on Bramble Cay), and some Australian incense (which wouldn’t light in the stormwinds of Edinburgh in February). The frustrations, dead ends, ineptness and questing for meaning is what I know to be grief work. It is a process to enter that only gives partial outcomes, and usually leaves you somewhere (else).

Despite the perceived increase in eutrophication (and sugar content) of the already heavily polluted pond, the freezing conditions, and the herd of swans, we launched the tray, which floated out on the strong westerly into the mid distance and sank gradually beneath the water. My friend said it was like watching a feeling happen.

As I struggled with the process of representation I faced the futility, cost and projections in my task, I was able to ignore or avoid my own decay, overfeed my domestic guest rodents, and engage with what go missing with extinction. The answer as the ecologist, Daniel Jansen* says in terms of biology, and the anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose echoes in human terms, is an opportunity to connect, potentially or actually.

As my work sank under the water, unnoticed by the rest of the world, I felt something of that loss. I may have murmured melomys rubicola under my breath without needing to know exactly what it meant.

As we looked for a site for extinction day commemorations I checked out the National Museum of Scotland (NMS). I had only a mild hope that I might find a melomys amongst the stuffed animal collection. What I did find was a display board listing some animals which had become extinct – which did not include the melomys or indeed any other animals which had disappeared since 2010. Which gave the commemoration another more practical focus.

The list of extinct animals I was then to send to the NMS ( including only mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and freshwater fish) covering only the years 2017-19, and based only on two reputed websites and a cursory check of the IUCN Red List data base, contained 25 names. It excludes those creatures which live on only in human captivity, which we are best able to watch die out (like the Northern Rhinoceros or the Spixx Macaw). Some of the species have been declared extinct more than once, as a specimen occasionally blunders out of the undergrowth in some unlooked-for place (usually at around the time it is being levelled to make way for human activity). Others were only ‘created’ as species after they were gone. So its not really an exact science, but really neither is speciation, which is looking increasingly like an Anthropocene construction.

But what is not in doubt is that many, many types of animals are disappearing and that everywhere in the world the trend is for a reduction in variety and overall number of non-domestic animals. We are living in an age of mass extinction, which human activity is ultimately responsible for. For most of our existence as humans we acknowledged our kinship with other creatures, and it is only in the transformations to capitalism that philosophy and science have created these divisions (and which belatedly both are now striving to close).

To see extinction as a hyperobject is to see it extending, largely unnoticed, into numerous dimensions of existence. Some of these are exemplified in the specific losses noticed by Jansen and Bird Rose – the destabilisation of ecosystems (one wonders what is happening to Bramble Cay without its main herbivore, for example) and the loss of cultural resources (for example the oft-quoted Lost Words which have vanished from the everyday vocabulary of our children), and others are there buried in our psyche. We watch wildlife documentaries, are shamed or activated by images of turtles with plastic around their necks , and maybe are beginning to perceive morality in terms of reducing our environmental impact (or reacting against those perceptions in aggressive, nationalistic justifications of our privilege).

Around us a shadow army of pets, parasites and animal crops provide us with a distorted connection to that legacy. We are becoming used to finding our friends grieving their pets, upset by the truth of food production, or shocked by the running over of roadkill. Grief is, after all, grief, and I suspect that the central part of it is the shock of how fragile life is. Our life.

After some correspondence and a brief protest action the NMS offered me a dialogue about how they commemorate extinction as part of climate change. Can I ask them to do it absurdly? I’d like there to be a way in which connections disappear, and the visitor is left increasingly in a void. Ideally this might be subtle, but colour and noise or smell would disappear. Or there is a game where it becomes a choice of what to save, but the choice has unintended consequences. Or they could suddenly find that all the exhibits in the lower level are under three feet of water.

I realise now that I am going to have to end the article. And in doing so I will feel the loss of the Bramble Cay Melomys, and the rich connections I’ve had from virtually knowing them. And I will also remember the list of the other known, unknown animals which I’ve learnt about after their end. And think about the unknown, unknown animals I haven’t learnt about. Yet, or more probably, at all. And now I see the image of Sadness from the film Inside Out, who I think should be there to meet us at the exit of the new exhibit. I’m with her now.

* What escapes the eye when species go extinct is a much more insidious extinction – that of ecological interactions.

Ewan Davidson lives in East Lothian. His blog is River of Things.

Fig.2: Museum specimen of the Rodrigues day gecko. Image Wikimedia Commons by Jurriaan Schulman

Fig.2: Museum specimen of the Rodrigues day gecko. Image Wikimedia Commons by Jurriaan Schulman Baiji by

Baiji by